Equisetum is a group of plants categorized as a fern that are often found in wet places. It superficially blends into the “grass-like” background of a wetland around rivers or marshes. This group is otherwise often called horsetails with 15 species found worldwide. There are four species most commonly found in the Klamath Mountains including Equisetum arvense (common or field horsetail) which happens to be the most common horsetail in the world.

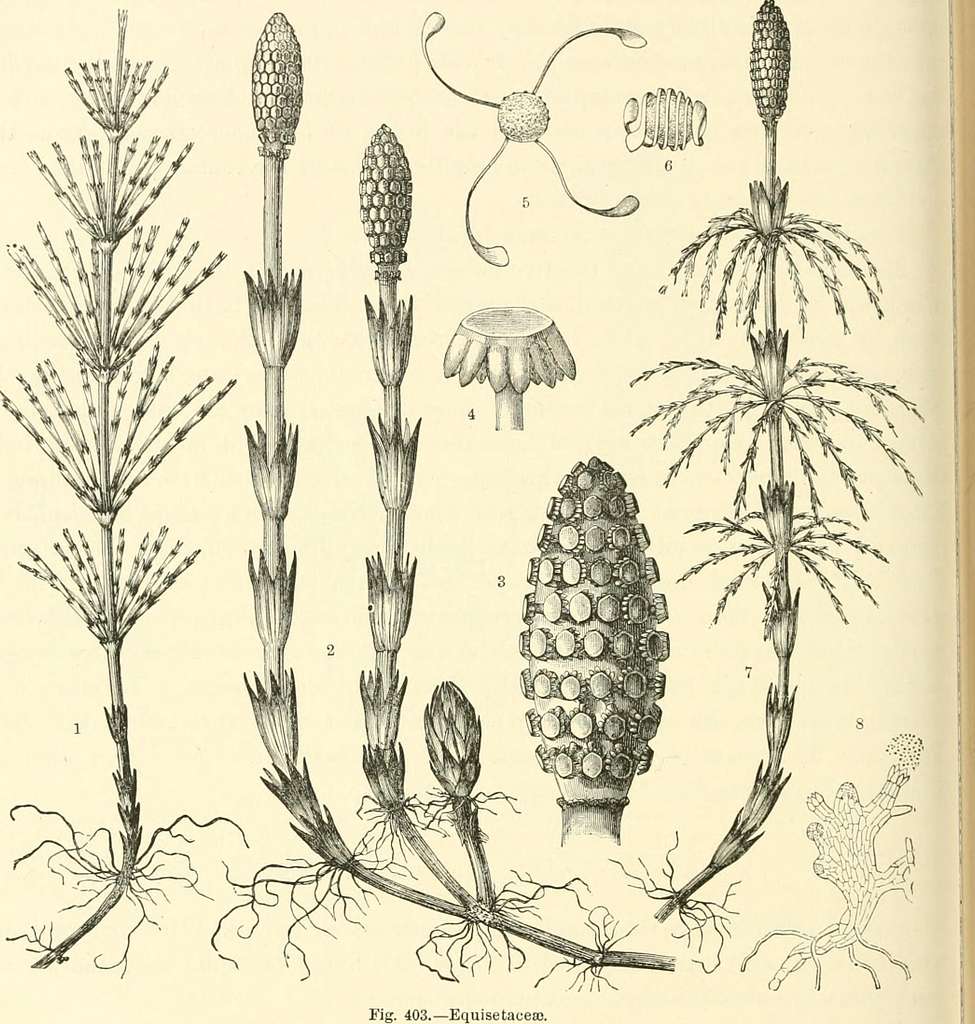

In 1883 a prominent plant taxonomist, August W. Eichler, divided the plant kingdom into two groups: Phanerogamae which reproduce by seed (via flower or cone) and Cryptogramae which reproduce via spore. The Klamath Mountains have an incredibly diverse existence of terrestrial cryptograms, which are represented by mosses, liverworts, lichens, ferns, forest mushrooms and algae [1]. As you may have deduced from the list, moisture plays a key roll for reproduction of a cryptogram. Classified within the fern family, the horsetail arrived on earth approximately 375 million years ago. The modern genus, Equisetum is a “living fossil” of the subclass Equisetaceae, which for 100 million years dominated the understory of Paleozoic forests [2]. The ancient genus ranged from large trees to the more modern low lying species we commonly see today.

For perspective, current evolution of hominids is understood to have occurred 55 million years ago, so our oldest hominid relatives likely also interacted with this plant. Features from this group are considered to be the early origins of plants known as “vascular” plants, which have cells specialized for holding water and minerals and moving them up and down through the ‘body’ of the plant.

Functionally, Equisetum is rhizomatous – meaning it has more than one way of reproducing. Sideways roots spread the same plant horizontally in the ground in addition to the little spore-bearing “cones” (strobili) which allow it a mechanism for sexual reproduction.

Most commonly you’ll see the plant spread, or propagate, along the river by being scoured out of the ground by high flows and wadded up with leaves, wood, and sediment deposited along the river bar. This is a natural process for plants to establish along depositional areas (sediment accumulation areas) freshly created along the banks of a dynamic river.

Reproductive spores of E. arvense have four ribbon-like appendages sensible to moisture. These “legs” fold back around the main body in humid air and deploy upon drying. Check out a video of this process below!

The sections of the plant are jointed and clasping each-other with little “frills” which are the true leaves of the plant. Find these leaves at the many joints which make up the stem. These little joints can be popped apart and the inside is rough, hollow and crunchy. The interior of the stems are made up of strong, lengthwise ridges that have been documented as being useful to scour materials like arrows, as well as polish metals and musical instruments [2].

Photo: Equisetum found along the Trinity River. [Simone Groves, Hoopa Valley Tribal Fisheries]

I first began deepening my relationship with this plant when I worked on a farm and met a gentleman there who spoke only Spanish (no English) and when we discussed the name for the plant, he called it by the direct translation of the common name that I knew for it “horse-tail” which is “cola de caballo” in Spanish. This piqued my curiosity as it seems like the common name is a unifying force. The Latin name is also derived from the same meaning “equus” (horse) and “seta” (bristle) and the term equisetum has been known to be used since the 15th century.

This plant is known in herbalism as an “archaeological vestige” of times immemorial. Indigenous uses are documented throughout the farthest reaches of land on our earth, including the northernmost tip of Greenland and Alaska, down to the southern tip of Argentina and Chile and the African continent as well. It can be found on islands completely isolated from the main land masses. It’s a pretty amazing feat in the plant world to have such a dynamic habit to survive under such varying conditions!

This plant has been catalogued by all of the first naturalists and medics attempting to collect together the resources of plant knowledge for indigenous plant use of early Europe including, Pliny the Elder in his book Naturalis Historia-Natural History. It is agreed upon that this plant can be consumed to help with hemorrhages, dysentery, diuresis, respiratory clarity, and internal cuts and hernias. It is also thought that the juices can be a good eye medicine for sore eyes, and some tribes have used it for treating fevers. The astringent qualities of the plant are thought to constrict tissues and provoke elimination of liquid. A total of 229 chemical compounds are isolated from the plant and used in contemporary medicines. Additionally, the silica in the body of the plant is a great, gentle exfoliant for your skin, or for washing dishes while camping.

Sometimes this plant group can be found as a common weed in your garden. Usually, when you see this plant, it’s an indicator of compacted, and anaerobic (lacking-oxygen) soil conditions. This can happen due to compaction from roads, or due to water-logged conditions, or where water is pooling for long periods of time. Water displaces oxygen by filling up the holes or pores in the soil and this makes it hard for plant roots to ‘breathe.’ Equisetum has a specialized cell type called ‘aerenchyma’ which are separate cells in the plant body for storing oxygen. This helps the plant be able to metabolize even when there’s no air.

Another unique characteristic of the Horsetail group is the silica mineral content in the plant body. Among all terrestrial plants, only horsetails require silicon as an essential mineral nutrient. Silica or silicon dioxide (SiO2) might be familiar to you as an important part of sand and crystalline quartz. Silica is an essential component of bones and organs and cartilage in human bodies. Water-born silica is the best way for various forms of biology to uptake silica and use it. Equisetum is the perfect plant to perform this function in the landscape.

For those interested in creating natural fertilizers for your garden, Equisetum has some surprises. Korean Natural Farming is a technique for amplifying native micro-organisms (bacteria, fungi, nematodes, and protozoa) to increase soil fertility. One Korean Natural Farming technique is to create a Fermented Plant Juice by breaking up plant material and allowing them to ferment. How can you make your own silicate rich fertilizer in your own back yard? In my personal experience it takes about 1 week for your fertilizer to be ready, and it is best to use Equisetum during it’s peak growing season, from April to July. Break up pieces of horsetail and place it in a bucket, or container, ¼ full is plenty of material to be effective, and fill it up with water. Let this bucket sit for 5-10 days (depending on temperature) and when you see bubbles appear in the water, it’s ready. Sugar can be added to increase the “vigor” of the ferment. When you see bubbles, the water can be poured on your garden. This water also smells remarkably like horse manure! Which has led me to question the multiple origins of the etymology of its common name.

References

- Garwood, J., Kauffmann, M. The Klamath Mountains A Natural History. Backcountry Press. First Edition. 2022. Pg. 167.

- Equisetum. Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia [Equisetum – Wikipedia]

- Native American Ethnobotany Database. Equisetum arvense L., [http://naeb.brit.org/uses/species/1421/]

- Online Etymology dictionary

- equisetum observations on iNaturalist

- American Herbal Products Association

- Sureshkumar, J., et al. Genus Equisetum l: Taxonomy, Toxicology, Phytochemistry and Pharmacology. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, Elsevier, 18 May 2023.

- Kundu, S. et al. Evidence of the oldest extant vascular plant (horsetails) from the Indian Cenozoic. Science Direct Plant Diversity. September 2023

- Cho’s Global Natural Farming

- KR;, Martin. The Chemistry of Silica and Its Potential Health Benefits. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, U.S. National Library of Medicine, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17435951/. Accessed 10 Apr. 2025.

Simone Groves, Riparian Ecologist, Hoopa Valley Tribal Fisheries

Simone is first generation California transplant of scottish descent raised in the unceded territories of the Raymatush in the rural west peninsula of the SF Bay where farmers, farm workers and hippies form the heart of the small town. She graduated in 2016 from Humboldt State University with a BS in Botany and has worked in the outskirts of rural Humboldt county on Natural Resource and Land management since 2013. She is passionate about plants and their interactions with dynamic systems as a mechanism for relearning our human-landscape interdependence.