By: Simone Groves, Riparian Ecologist, Hoopa Valley Tribal Fisheries

Cattail versus Tule

Typha latifolia & Schoenoplectus acutus

Cattails may be one of the most familiar sedges with its endearing name and inflorescence (or flower), which looks like a corn dog perennially sticking out of the tall green walls of a marsh. However, the cattail’s cousin, tule (also referred to as bull-rush) occupies similar habitat yet is not able to persist in the languishing habitat conditions that emergent wetlands undergo today.

The world’s center of diversity for cattail is in Eurasia with 6 species found on every subcontinent. North America also has several different species (9 in North America) including 2 species native to California. Additionally, there are several species from the Eurasian subcontinent that can be found in North America, including locally, which have been shown to exhibit invasive behavior.

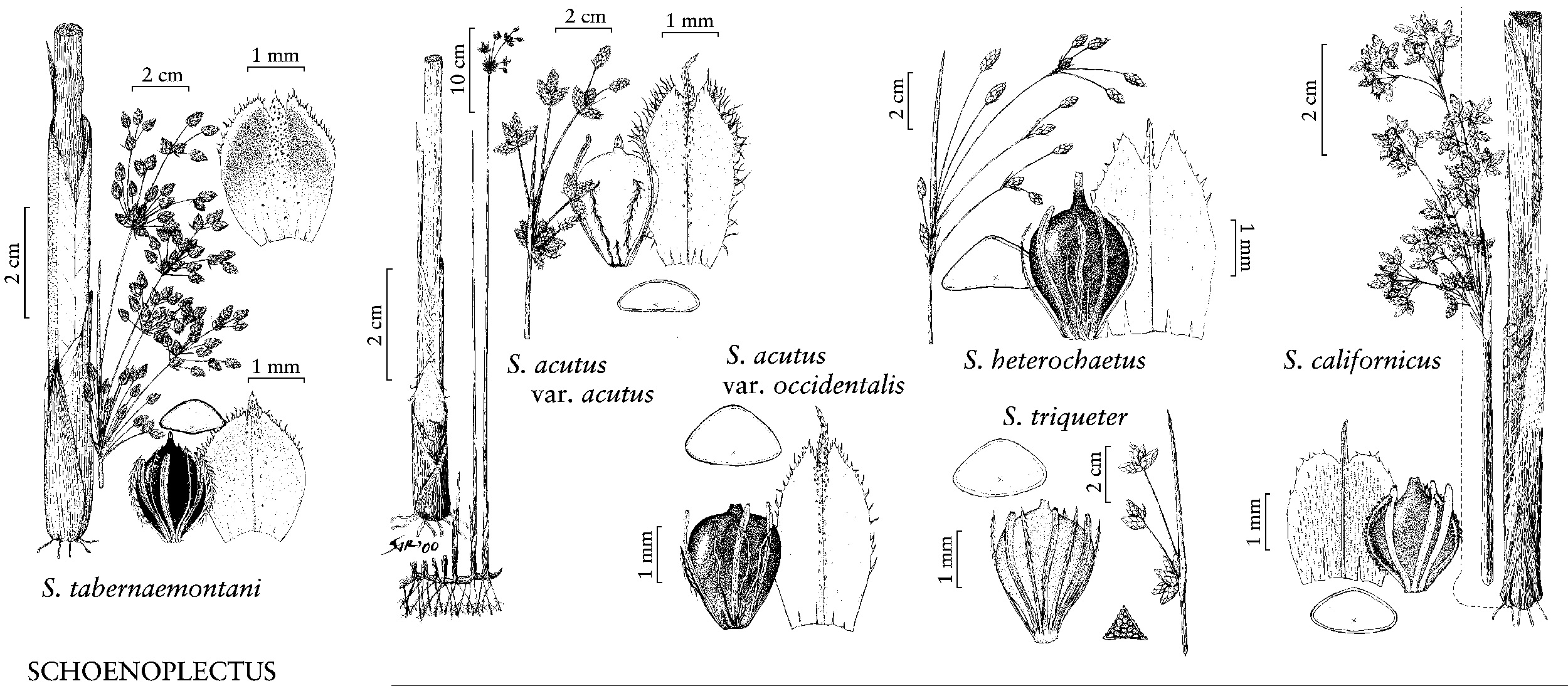

The most common species of cattail is Typha latifolia and the most common species of tule or bull-rush is Schoenoplectus acutus. Schoenoplectus or tule are represented by 25 species, 15 of which are on the North American subcontinent, and 9 of which are native to Californian wetlands. Schoenoplectus californicus and S. acutus are the large stature tule common in Trinity County.

Cattail and tule are both around the same ‘stature’ or blade height which represents the overall plant height, however there are several ways to tell the two apart.

Cattail has a wide flat blade that is arranged in a ‘fan’ like an iris. Looking at the leaves alone one might think that this species is an Iris. Tule has a round hollow leaf, not flat at all, which is unusual for a sedge! The typical saying for sedges is: “sedges have edges” and “rushes are round” but tule breaks this rule.

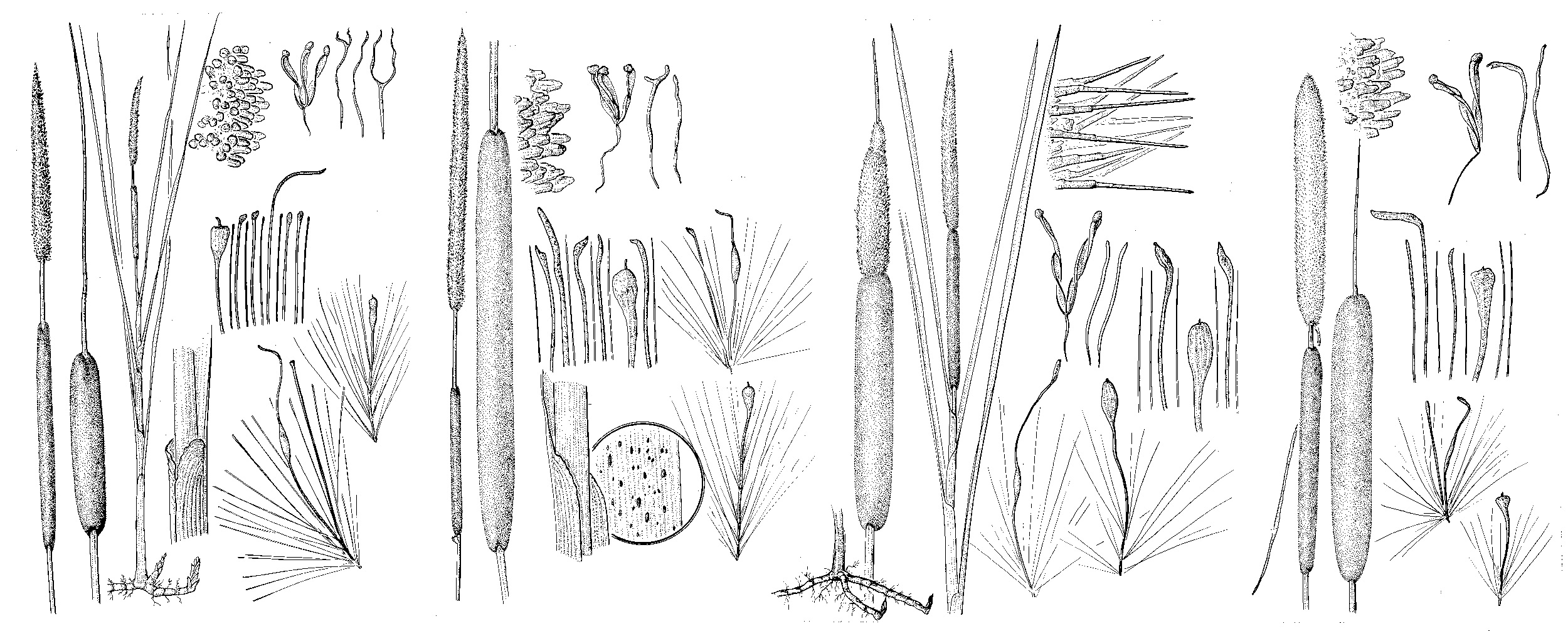

Also, the flowers of the plants look very different. With cattail, it’s common name is descriptive of the flower. In many sedge species, there is a male flower at the top of the inflorescence, and female at the bottom. The fluffy stuff that you’re used to seeing on a cattail is actually the seeds! Each has a separate wind-blown umbrella to help it land far away from the mother plant. Sometimes it can take a full rotation from fall to spring before the seeds will release from the corn-dog flower head, which can coincide with the nesting period for many birds. Cattail seeds are not very nutrient dense, but you might find birds harvesting beaks full of fluff to line their nests.

In tule, the seeds are born in a little toss of beads on the end of a string which emerges from the top of the tall, round leaf stalks. Tule seeds (in contrast to cattail seeds) are desirable as bird food, and songbirds in the marsh can often be found hanging crookedly off a tule leaf and eating the ornament of seeds from the top of the plant.

These plants both require slow-water habitat. Cattail can handle wider extremes of environmental conditions, such as more scour, a higher tolerance of both inundation and dryness, and a greater ability to establish from windblown seeds.

Tule on the other hand, requires backwater areas with very little scour, specific amounts of perennial inundation and cannot usually tolerate completely dry conditions (6). Oxygen is often the limiting factor for primary productivity in hydric wetland soils. This suggests that when tule experiences good growing conditions, it can facilitate survival of other oxygen-dependent species (which is typically considered more desirable for diversity in aquatic environments). Tule and cattail are often competitive bedmates and cattail will usually win the inexorable struggle when the two spar for habitat.

The Latin derivative for cattail, Typha, may come from the Greek word typhein, to smoke or to emit smoke; or typhe meaning “cat’s tail” but the true reason for using this Greek root is not known today. Some resources today often find these descriptions to be confusing because it is hard to understand why this plant might be described as ‘smoke’ unless one has a relationship between fire and wetland communities, and so, many people call it cattail because either interpretation could be an explanation for its name. This plant language offers us an opportunity to be curious and listen to others to unravel the answer.

Historically California tribes have an intimate relationship to wetland habitats. Many tribes will refer to the wetland as the “medicine cabinet” or “drugstore” as many species foundational to healthy living within ecosystems can be found in these habitats. Additionally, in California, burning would be carried out in wetland communities to help maintain the health of the tule and maintain the balance of this critical habitat for both ecosystem function and human health (9, 11, 12, 13).

European history documents cattail flower heads utilized as slow burning torches that were very smoky and may have helped to repel insects. Also, many historical references to “reed” are referring to cattail, including biblical references (21).

In local languages, the Hupa people describe tule as tł’ohtse’ (17). Karuk people describe tule as taprarahtunvêech for living plants or taprárah for the plant in use as a mat or sewn object (18). Yurok people describe tule and cattail synonymously as ‘wehlkoh meaning “leaves woven together to make a mat or raincoat” (24).

In plain English, cattail can also be called “bull rush” which leads us back to the reason why these two species are paired together in this article! How can we tell which “bull rush” is the true bull rush?! One of the great struggles with plants is the ability to communicate effectively about which individual is being described from person-to-person. This is a challenge that has been handed down through many generations and has led us to the current era of the California Jepson Manual and using dichotomous keys and Latin to separate different plant descriptions from one another. For this reason, the term “bull rush” or “rush” can be an ambiguous description, but for this article it is important to create distinction.

The fossil record of cattail can be traced back to the Paleogene part of the Cenozoic, which is when non-avian dinosaurs went extinct. This era is marked in the geologic record by the iridium anomaly along with the deposition of several other transition metals which can be toxic for animal consumption. This was at the same time as mammalian and vertebrate diversity expanded dramatically and the circumpolar current began to form. Both cattail and tule can bio-accumulate toxic minerals and provide filtration for slow water habitats. One can imagine how this may have supported survival of new life in a stressful environment (23).

Both humans and animals have a long history of using cattail and tule. All parts of both of these plants are edible at various life-history stages (10, 14, 15). The roots of both plants are thick and starchy and have been harvested, cultivated and tended by ancient humans before agricultural practices began. The mashed-up starch can also be used to staunch bleeding and disinfect wounds.

Cattail shoots are usually harvested when young. They look and feel like a leek and have a similar texture when cooked, with a milder flavor. The pollen is high in protein and can be used like flour to thicken soups or make pancakes. Stems of cattail can be made into a tea to treat whooping cough (16). The fluffy seeds of cattail have been used as diapers, sanitary napkins and for dressing wounds by humankind worldwide with it’s soft absorptive features.

Tule’s young shoots can be eaten like asparagus but mature leaves can act as an emetic, causing vomiting. Tule’s most famous use is for fiber. Many tribes throughout California in particular have used tule leaves for houses, weaving sleeping mats and roofing for houses as well as tule boats (22).

Tule and cattails provide very important habitat for birds in particular. Beyond a source of sustenance, wetland birds also use these habitats for the edge effect that they create for protection. The aerial friction that these plants provide, creates a buffer from extreme weather conditions within the boundary layer of a wetland, which is typically a pretty exposed environment. Both of these species can be used in botanical wetland delineation to establish protected habitats (23).

Both cattail (Typha latifolia) and tule (Schoenoplectus acutus) play vital roles in the ecology of wetland environments, serving not only as crucial habitats for various wildlife but also as important resources for human communities throughout history. Their unique characteristics, from the distinct morphology of their leaves to their varied reproductive strategies, highlight the biodiversity present within these ecosystems. Furthermore, understanding their ecological functions and cultural significance can foster greater appreciation and stewardship of wetlands – a critically important yet declining habitat area within our watersheds.

Resources

- Native American Medicinal Plants: An Ethnobotanical Dictionary by Daniel E. Moreman

Simone Groves, Riparian Ecologist, Hoopa Valley Tribal Fisheries

Simone is first generation California transplant of scottish descent raised in the unceded territories of the Raymatush in the rural west peninsula of the SF Bay where farmers, farm workers and hippies form the heart of the small town. She graduated in 2016 from Humboldt State University with a BS in Botany and has worked in the outskirts of rural Humboldt county on Natural Resource and Land management since 2013. She is passionate about plants and their interactions with dynamic systems as a mechanism for relearning our human-landscape interdependence.