A tiny parasite in the Klamath & Trinity Rivers

What is C. shasta?

Ceratonova shasta (C. shasta) is a microscopic parasite that is native to rivers of the Pacific Northwest, including the Klamath and Trinity Rivers. Infection is most severe for juvenile salmon but can impact returning adults as well. The impact of an infection is highly influenced by water conditions like temperature, flow, and seasonality. If conditions are right for the parasite’s host worm, C. shasta can rapidly proliferate and lead to severe infections that can be devastating to populations. In 2021, after years of drought that impacted river conditions juvenile salmonid deaths from C. shasta in the lower Klamath reached into the hundreds of thousands [1, 2].

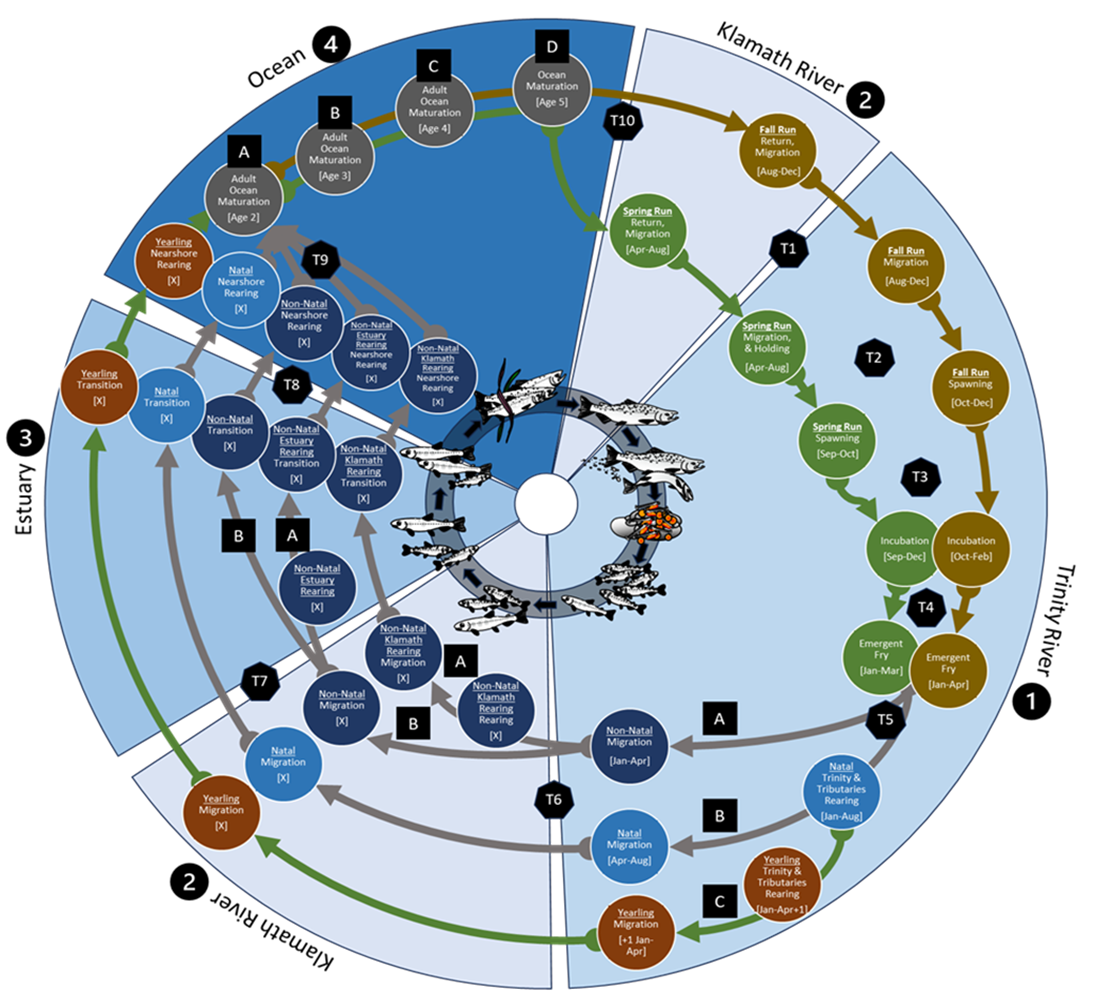

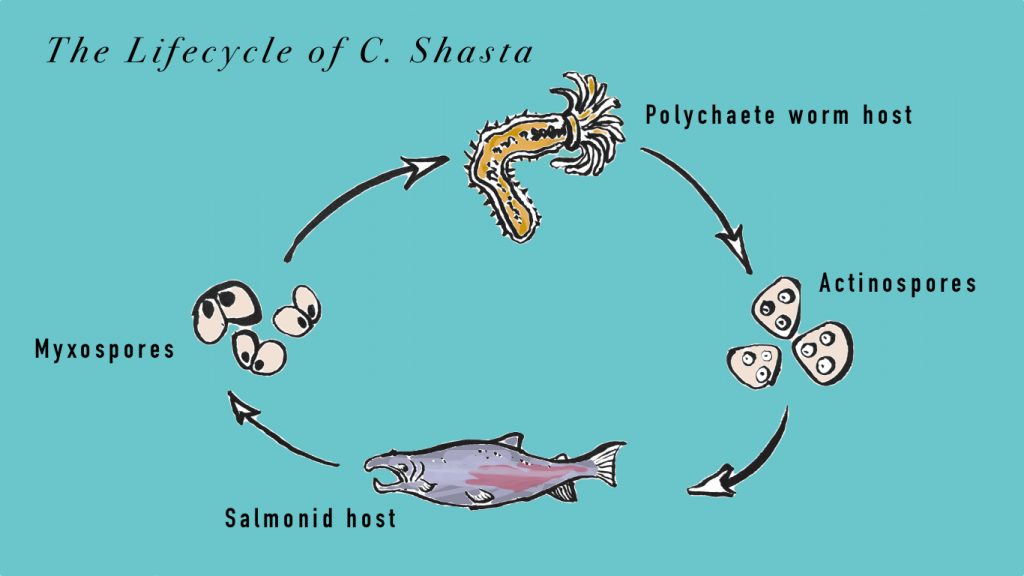

To survive, C. shasta needs two hosts

1. A carpet of tiny worms

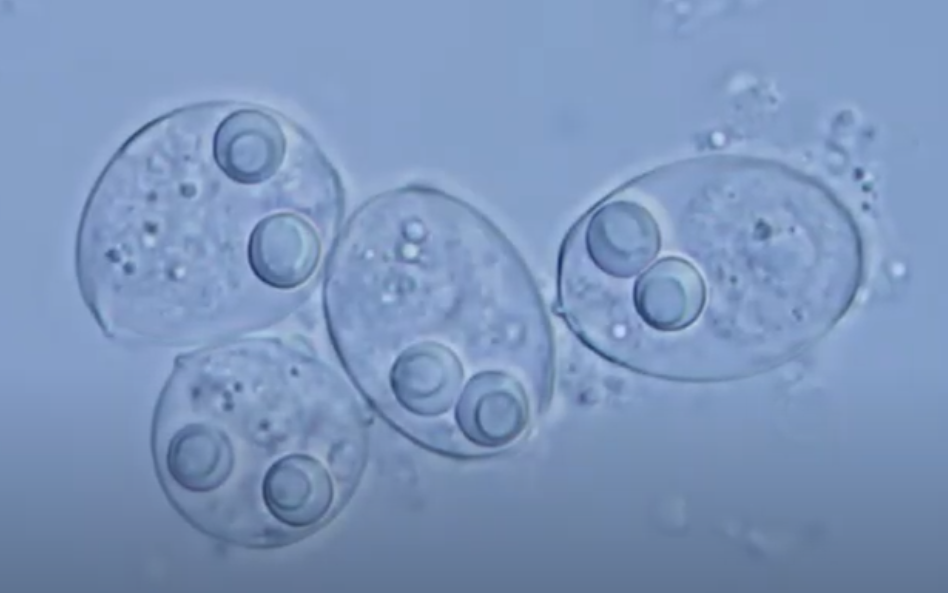

C. shasta starts its life inside a freshwater worm, called Manayunkia occidentalis. The worm, smaller than an eyelash, lives in mud and on rocks below the surface of a river or reservoir in colonies that can resemble an underwater carpet. Inside the worm, the parasite grows and turns into a new form called an actinospore. Once an actinospore, the worm releases the microscopic parasite to float in the water column and wait for its next host [3].

2. Salmon and Trout

As they swim young salmon breath in the actinospores allowing the parasite to attach to the gills and then enter the fish’s body. The parasite then travels to the fish’s intestines, where it multiplies and causes internal damage. This makes the fish sick and weak, causing many to succumb to the infection. The cycle continues when infected fish (including adults) release more spores back into the water after they die.

Are Adult Salmon Affected?

Adult salmon can be infected with C. shasta however the severity is influenced by other stressors. Typically, adults encounter the microscopic spores during upriver migration through areas with high spore loads (like the lower Klamath River during spring/summer). If the fish is stressed from high water temperatures, poor conditions or other pathogens, C. shasta could lead to pre-spawn mortality or failure to spawn. Although typically resistant, if infected, adults can act as a carrier of the parasite – shedding spores when they die and decompose. If the spores are shed in a system that does not have adequate flushing flows during the ensuing winter months, juveniles from the area could be affected. While some disease impacts to adult salmon are possible, if conditions in the river are favorable, adults are generally more resistant to effects of the disease than juveniles.

The Klamath River

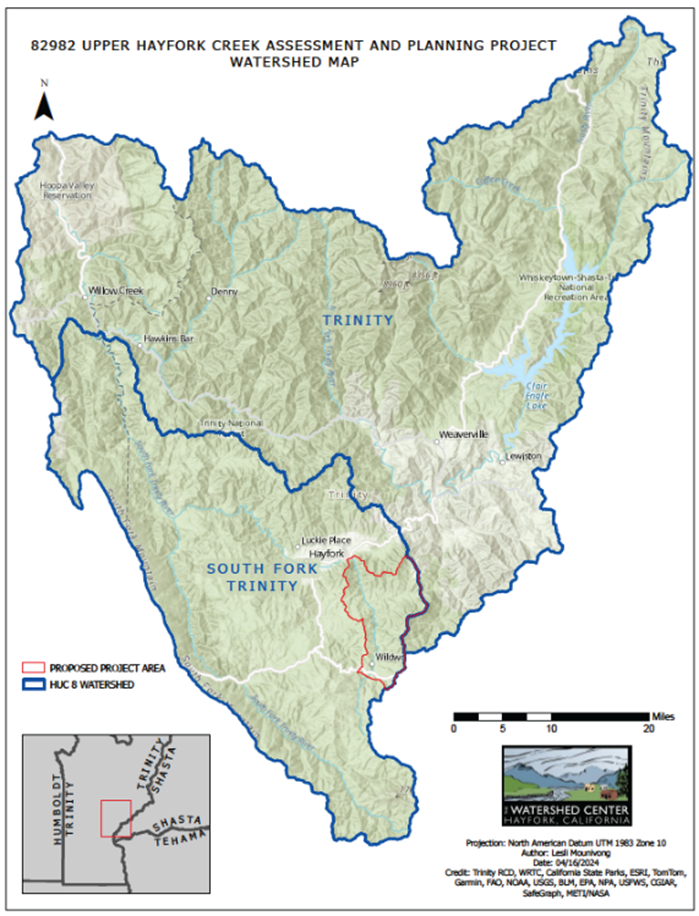

Salmon health and vitality is of utmost importance for Klamath indigenous groups like the Yurok, Quartz Valley, Karuk, and Hoopa Valley Tribes. For millennia salmon have provided sustenance and are celebrated as integral to the health of people, culture, tradition, and economy. The continued decline of salmon due to C. shasta and other human-enhanced factors are deeply felt by local people and led to the decade’s long advocacy to remove four hydroelectric dams on the Klamath River.

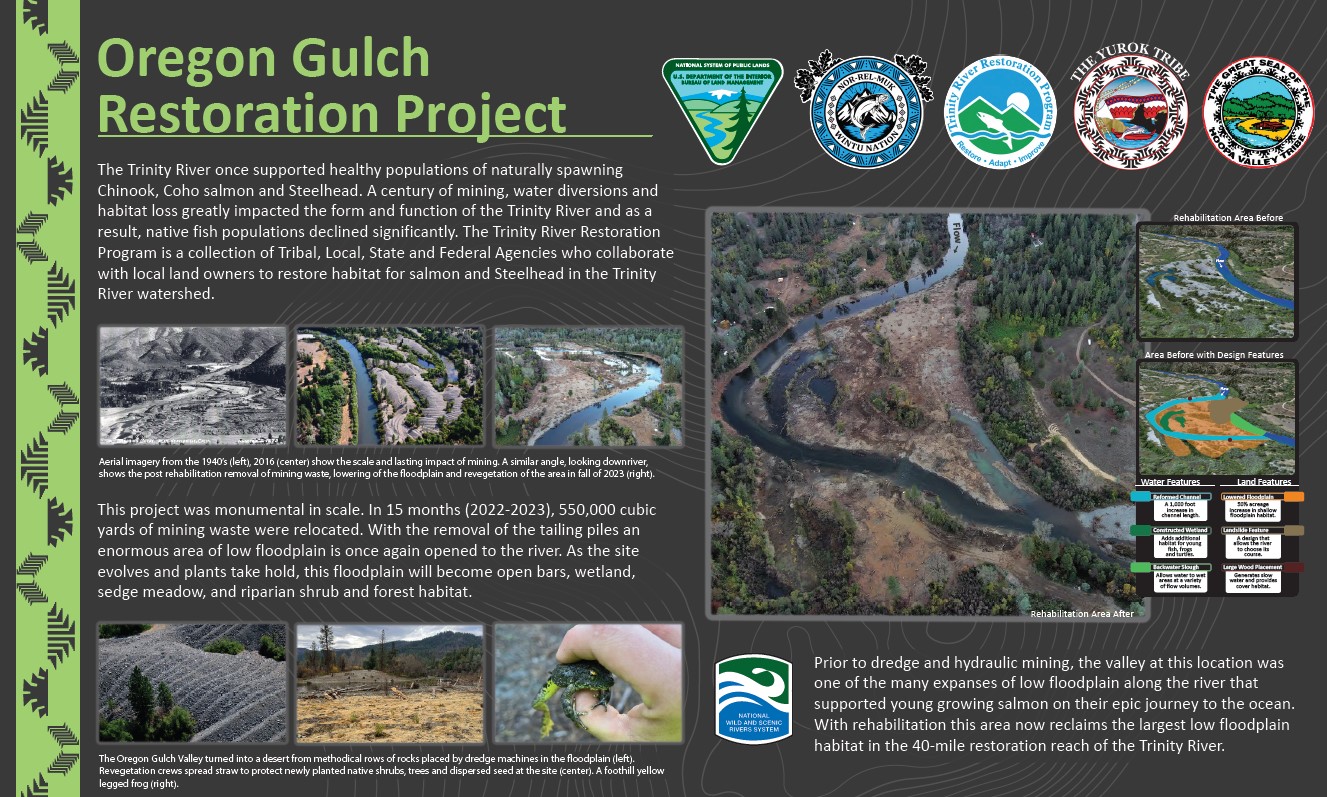

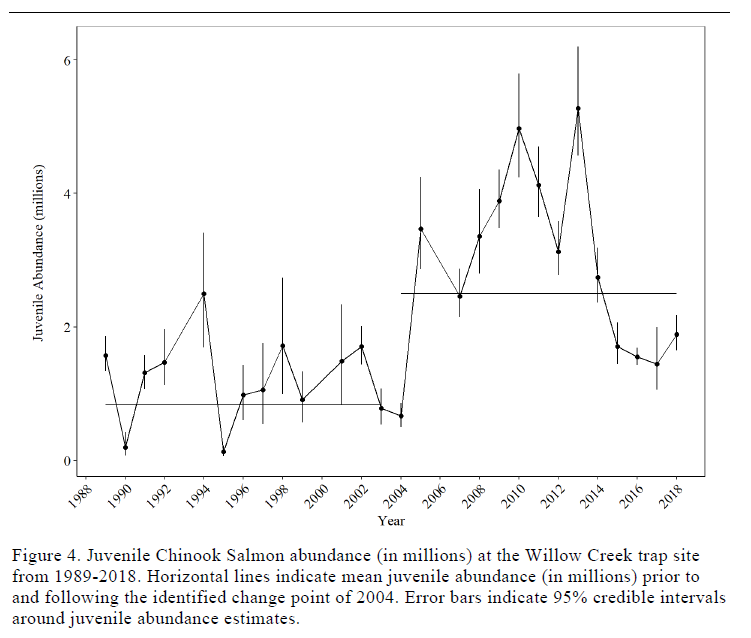

In 2023 and 2024 these dams on the Klamath River were removed, allowing salmon, steelhead and lamprey to reconnect to 400 miles of spawning habitat. It is the largest dam removal project in U.S. history, to date. Ecological goals for dam removal are to improve water quality, restore resources to Klamath River Tribes, restore habitat for salmonid species, and improve the health of salmon and steelhead [5].

The Klamath River is home to several salmon species that are important to Native American tribes, commercial and recreational fishers, and the ecosystem as a whole. Although infections occur in all species of juvenile salmon or trout, if the parasitic worm host is allowed to thrive, results can be devastating for some salmon species. One such species of concern are Coho salmon, which are recognized as “threatened” in the Klamath and the Trinity and are especially vulnerable to population scale impacts from large scale fish kills propagated by parasites.

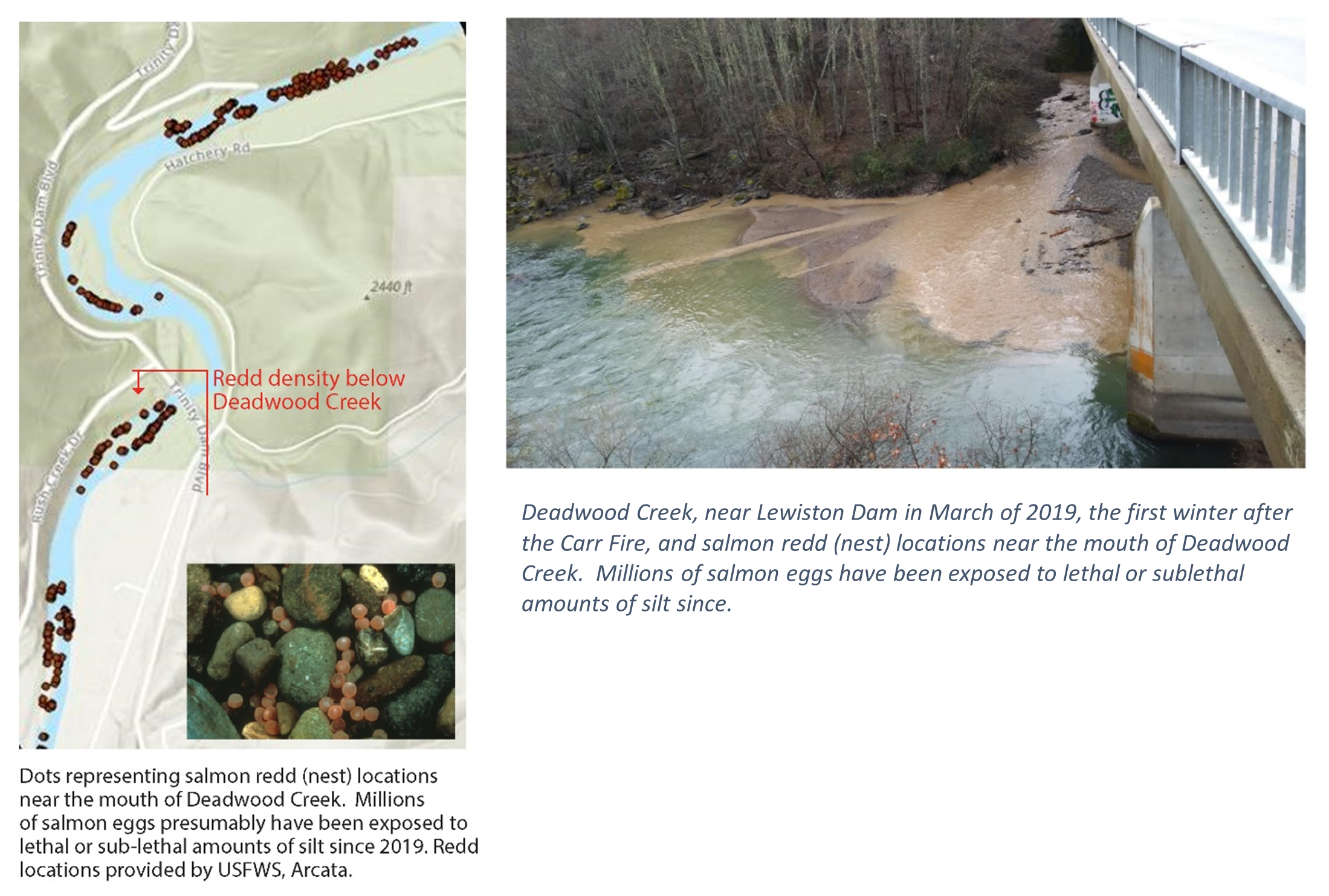

What made the lower Klamath River a hotspot for C. shasta? Below Iron Gate dam, the primary reasons were twofold. First, scouring events from winter storms were blocked by dams failing to disperse sediment. Second, waters held in several chains of reservoirs warmed. Ultimately these combining factors led to robust habitat conditions for the parasite’s aquatic worm host. Fish heath experts in the Klamath Basin are hopeful that dam removal will mitigate previously favorable growing conditions for the host worm [6]. Removal of JC Boyle, Copco 1 & 2 and Iron Gate dams will allow for a more natural flow of water from tributaries and potentially help to scour growth of the host worm with winter storms.

Hope for Trinity River Fish Populations

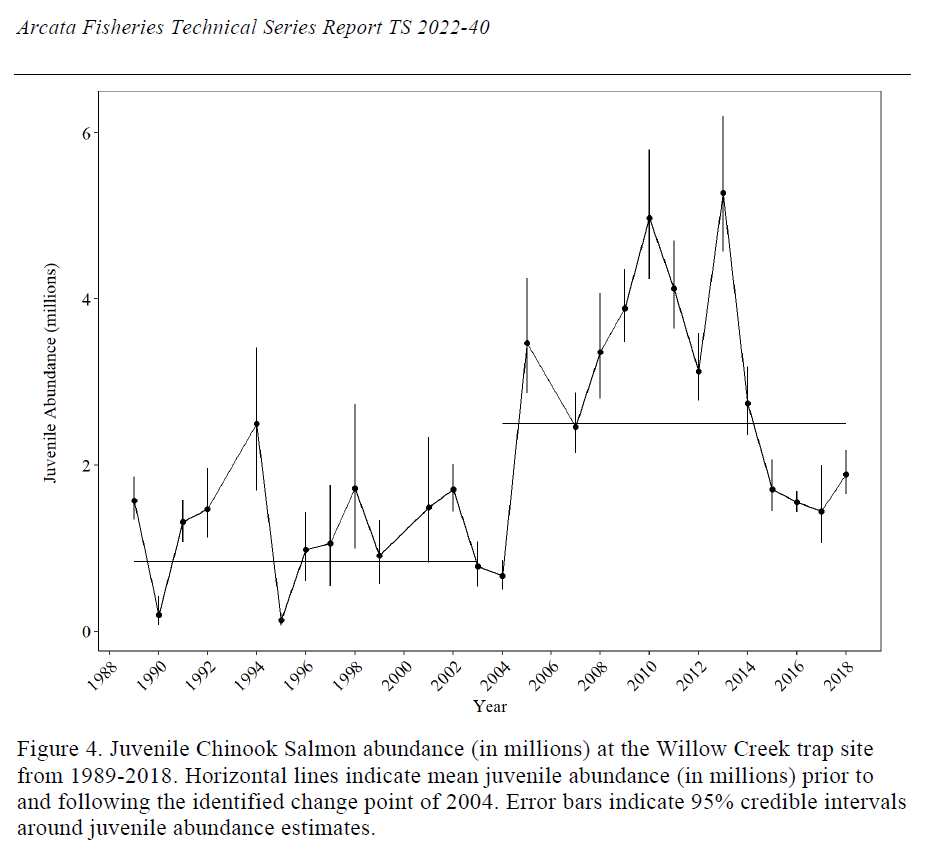

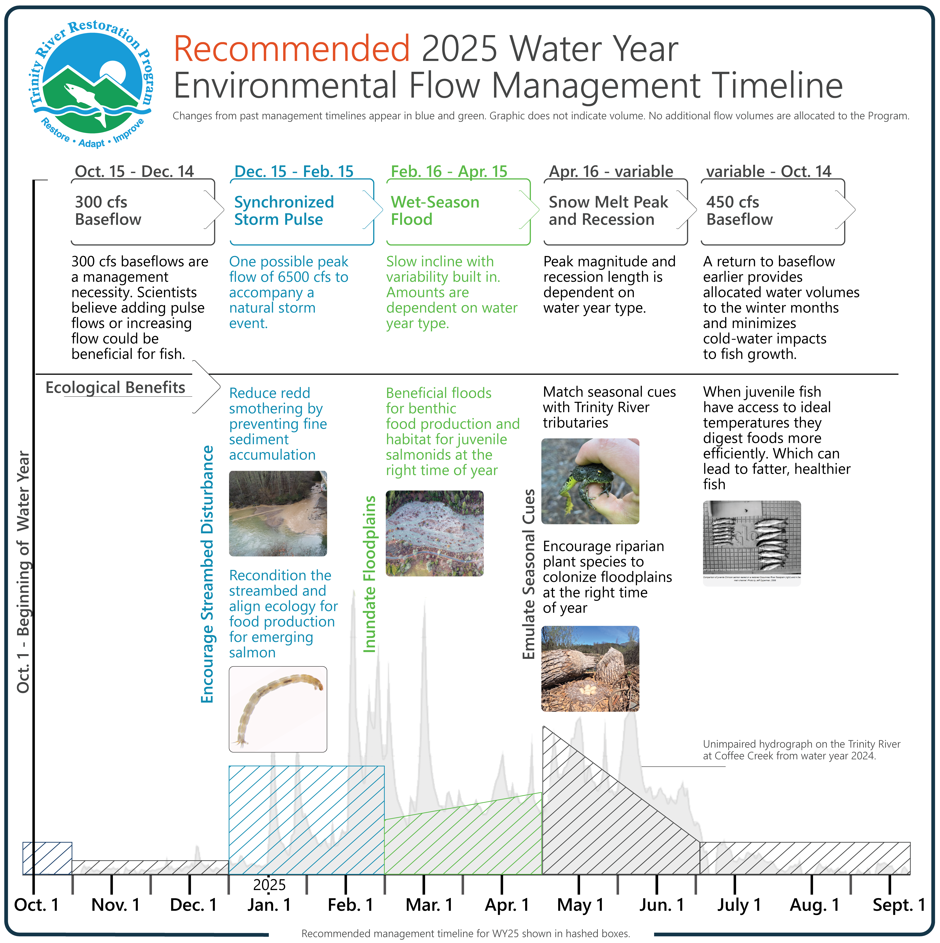

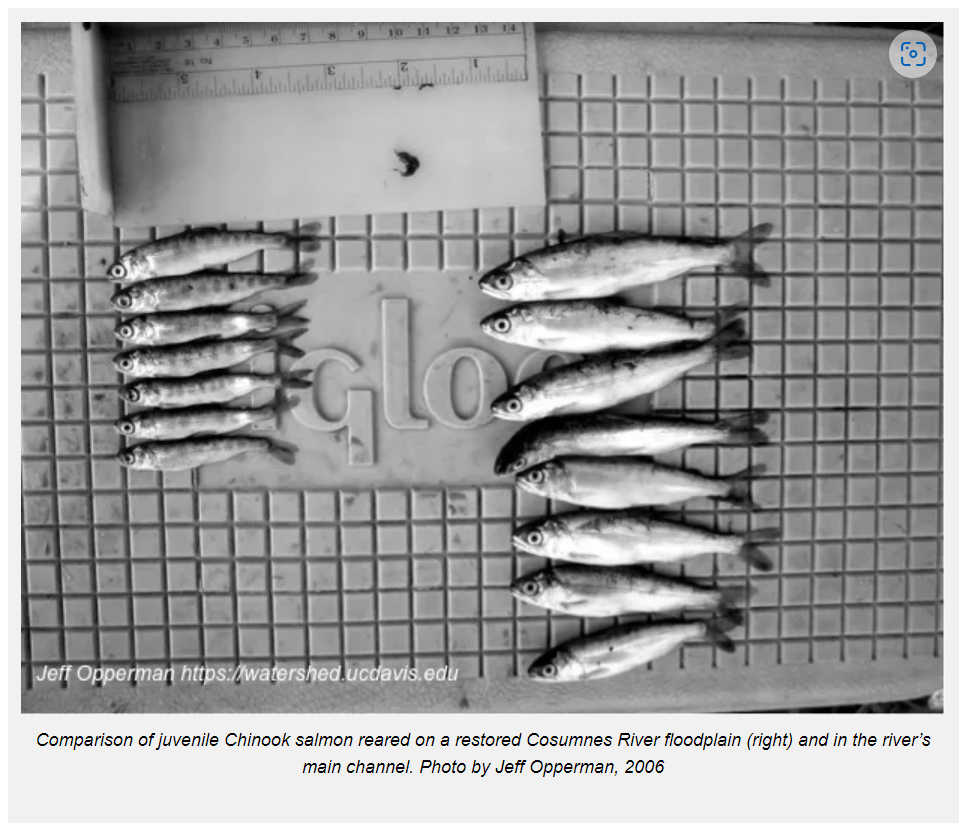

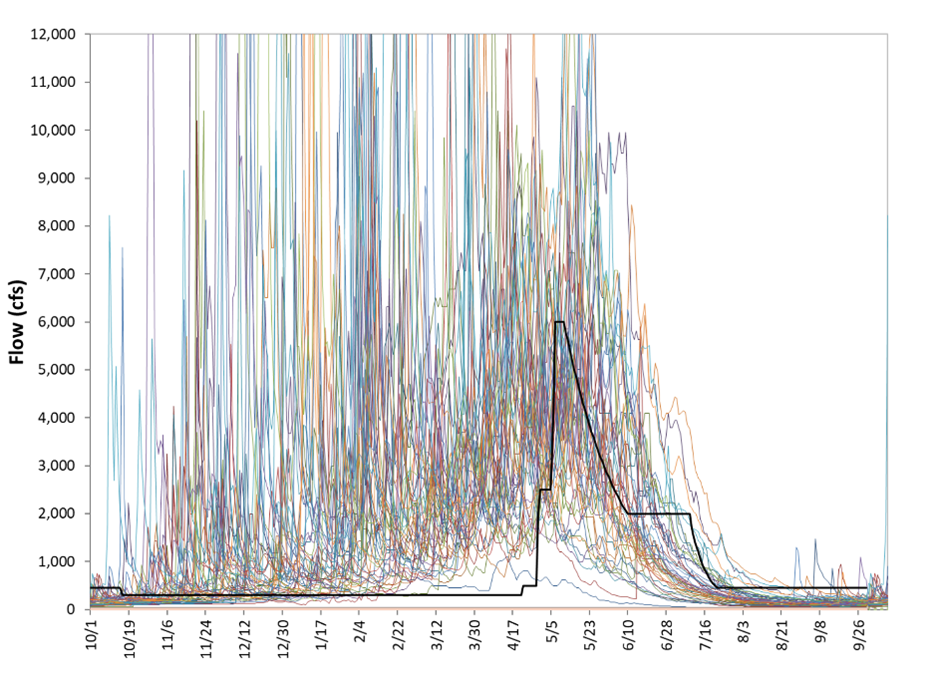

The Trinity River joins the Klamath River approximately 44 miles above the ocean, so its fish are subjected to the conditions of the lower Klamath River during their migrations. Beginning in late winter juvenile chinook begin to migrate downriver feeding on drift invertebrates, resting and digesting in warmer slower waters. Once they meet the mild saline waters of the Klamath estuary, they begin a smoltification process where their bodies change and adapt from freshwater to saltwater. Cold temperatures and salinity may reduce progress of disease, but do not eliminate infection [1].

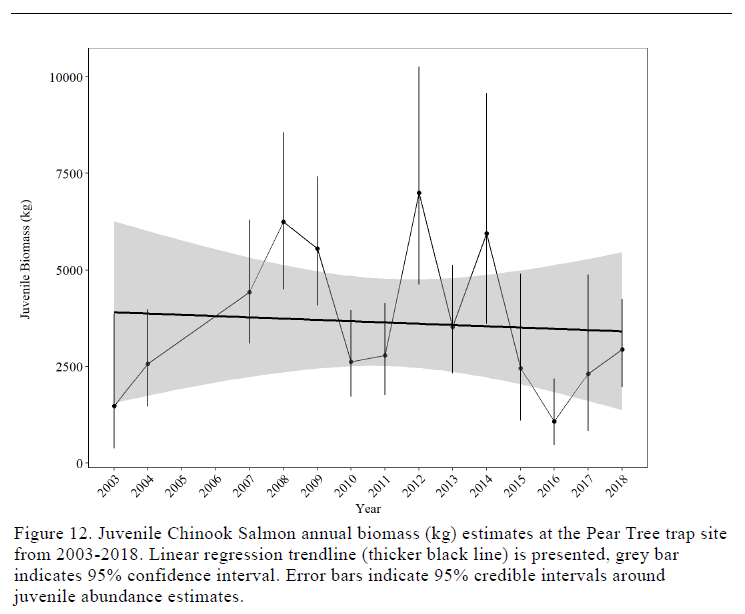

Because of their migration paths, Trinity River fish populations were part of the juvenile fish kill on the Klamath River in 2021. This event, along with historic drought conditions that followed, allowed for pathogens like C. shasta to play a significant role in returning adult escapement. Since most Chinook exhibit a 3-5 year life cycle, we’re still experiencing the loss of these juvenile fish today. Historically low returns of adult chinook salmon have prompted recreational fishery managers to close in-river salmon fishing seasons for a third consecutive year [8, 9]. Although the immediate impacts have been devastating for recreational anglers and river enthusiasts, there are many hopes (and also many unknowns still to be learned) following the removal of the dams. The primary hope for Trinity River outmigrant fish to experience less frequent and less severe infections once they reach the Klamath River so that juveniles as well as adults can manage natural stressors and thrive.

Klamath Fish Health Assessment Team

The Klamath Fish Health Assessment Team (KFHAT) is a technical workgroup which formed during the summer of 2003 with the purpose of providing early warning and a coordinated response effort to avoid, or at least address, non-hazardous materials related fish kill events in the anadromous portion of the Klamath River basin [10].

To accomplish this goal, KFHAT created a network of experts and monitoring efforts through which information about current river and fish health conditions in the Klamath Basin can be shared among participants, the general public, and resource managers.

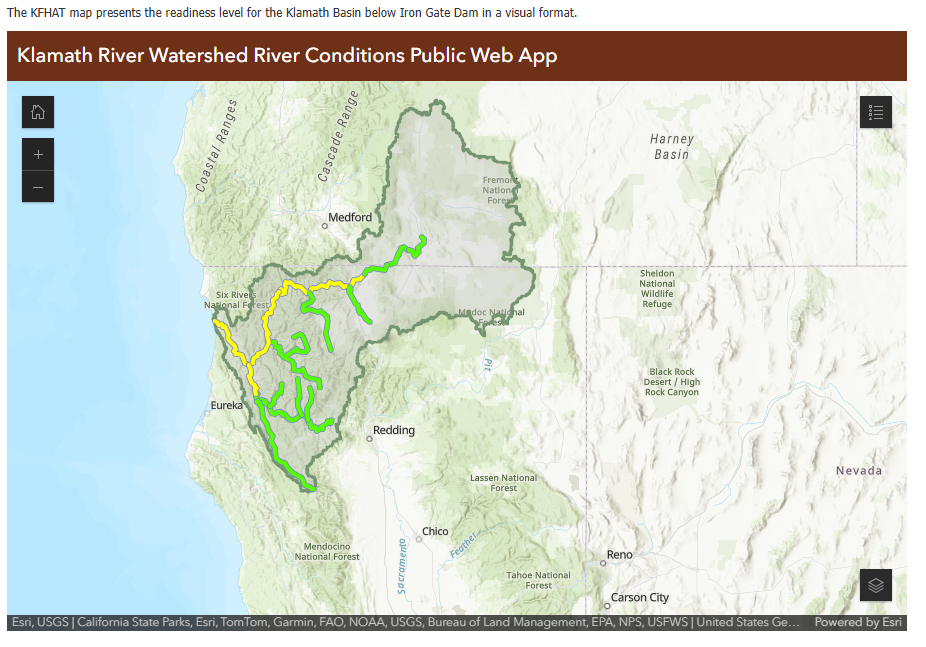

Every year, beginning in late April, members of KFHAT hold meetings to assess Klamath Basin fish health along the Klamath and Trinity Rivers and their main tributaries. The group publishes observations as well as a readiness level map based on those observations on a public facing website: Klamath Fish Health Assessment Team (KFHAT) after each meeting.

How are juvenile populations fairing this out-migration season? The wet winter of 2024/2025 has set the system up with favorable fish health conditions, but our area’s typical hot July weather can lead to stressful lower river environments. Thus far the 2025 monitoring season has seen some irregularities with regards to concentration of C. shasta. Klamath Basin water quality monitoring is implemented annually by a team at Oregon State University and recent monitoring results are showing higher than normal spore counts of C. shasta in geographic areas that are puzzling scientists [10]. In the lower river, screw traps are catching Trinity River hatchery-released yearlings from the fall and spring brood stocks with infections [10]. Although these conditions exist each year, they vary in severity and salmon evolved to this specific weather pattern. The species stay healthy by seeking cold water refugia located in deep stratified pools and cold-water tributary mouths during the hottest weeks of the year. Also typical to the area, wildfire can aid conditions when smoke sits in drainages, reflecting the sun’s heat back into the atmosphere and therefore cools air and water temperatures.

Although this year’s conditions thus far are concerning (note the yellow readiness levels in the map above), many juvenile salmon are in the last stages of migration to the ocean and are likely in the lower Klamath river undergoing smoltification or learning to live in their new ocean environment. What will conditions be when they return to spawn in our river in 2028, 2029, or 2030? Of course, only time can tell, but with the removal of four Klamath Dams, river managers are hopeful that, when it comes to controlled conditions, Trinity and Klamath run salmonids will have a more favorable environment than what populations have encountered for over six decades, and they might be more favorably armed to withstand what mother nature may bring their way.

Thank you to Dan Troxel, California Department of Fish and Wildlife lead on the Klamath Basin Fish Health Assessment Team and Morgan Knechtle from California Department of Fish and Wildlife for providing detailed edits to this article.

References

- As massive fish kill continues on Klamath River, Karuk Tribe declares state of climate emergency

- Serious fish kill consumes the Klamath River | Local News | heraldandnews.com

- Ceratonova shasta – Wikipedia

- Benefits of Klamath River Renewal – Klamath River Renewal

- TRRP: Fish of the Trinity River

- Dam removals, restoration project on Klamath River expected to help salmon, researchers conclude | Newsroom | Oregon State University

- Chinook Salmon Fact Sheet – U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

- Another Commercial Salmon Season Closure is Expected | News Blog North Coast Journal. April 22, 2025.

- CDFW News | Limited Chinook Sport Fishing to Reopen in 3 Central Valley Rivers, excludes Klamath Basin and Mainstem Sacramento.

- KFHAT_2025_Report_5.pdf

Further Reading

Key Parasites of Salmonids in the Klamath and Trinity Rivers

| Parasite | Type | Key Life Stage Affected | Impact Severity | Notes |

| Ceratonova shasta | Myxozoan | Juveniles | High | Major mortality factor in Klamath |

| Parvicapsula minibicornis | Myxozoan | Juveniles | Moderate | Common co-infection |

| Nanophyetus salmincola | Trematode | Juveniles & adults | Moderate | Common in Trinity River fish |

| Ichthyophthirius (“Ich”) | Protozoan | All stages | Variable | Outbreaks under warm conditions |

| Myxobolus spp. | Myxozoan | Juveniles | Low–moderate | Rare, possible underdiagnosis |

| Henneguya spp. | Myxozoan | Juveniles & adults | Low | Occasional gill infections |

| Gyrodactylus, Dactylogyrus | Monogenean | Juveniles | Low–moderate | Mostly hatchery-associated |

| Sea lice | Copepod | Smolts in estuary | Moderate | Not a primary river concern upstream |

Kiana Abel, Public Affairs Specialist

As Public Affairs Specialist for the Trinity River Restoration Program, Kiana manages external communications, media relations, and stakeholder outreach. She acts as a liaison between program initiatives and the public, transforming technical findings into compelling narratives that promote understanding of restoration initiatives on the Trinity River. Kiana holds a Batchelor’s in Art History, has spent most of her career in marketing and is focused at the TRRP on bridging the gap between public awareness and resource restoration and management.