Exploring Seasonal and Habitat Patterns of Trinity County Fungi

By: Kiana Abel, Trinity River Restoration Program. Article has been adapted from Kyle Sipes Science on Tap presentation, “Mushrooms of Trinity County: From the South Fork to the Scott Mountains“ January 28, 2026.

Trinity County, located in Northern California, provides a variety of habitats for wild mushrooms. Over 800 species of mushroom-forming fungi have been documented in Trinity County (iNaturalist). In January we welcomed Kyle Sipes, avid mushroom enthusiast, to present, “Mushrooms of Trinity County: From the South Fork to the Scott Mountains” at our Science on Tap event. If you missed his presentation and are interested in foraging for mushrooms, we hope to summarize the presentation here and share some of the tools for mushroom identification. Most notably, his presentation was structured around understanding preferred habitat, symbiotic relationships and key identifying features of individual mushroom types. In this article we hope to give an outline of mushroom hunting through forest types indicating seasonality, habitat details and identification tips. We will explore the life history of mushrooms to enhance understanding of their role within forest ecosystems.

Life History and Ecological Roles of Mushrooms

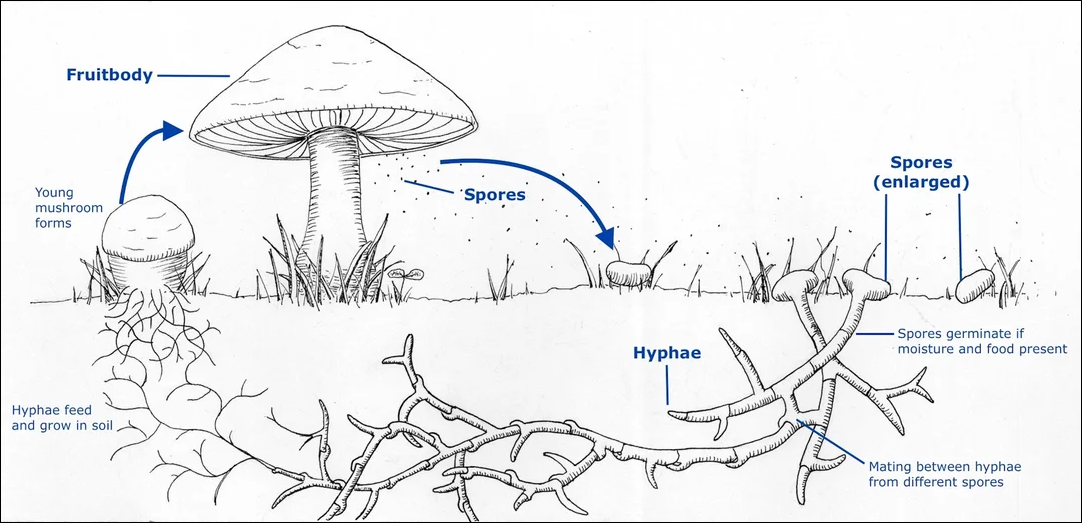

Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of fungi, and their life history begins with microscopic spores released into the environment. When conditions are favorable; adequate moisture, temperature, and a suitable substrate, these spores germinate into thread-like structures called hyphae. Hyphae grow and branch underground to form a network known as mycelium, which is considered the main body of the fungus, not the fruiting part that we see above ground.

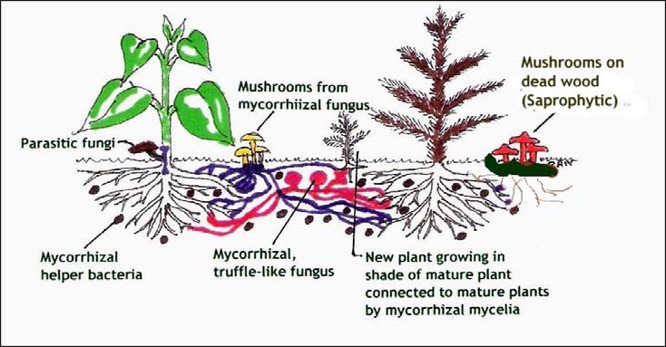

From there, fungi interact with their habitat either as a decomposer, in a symbiotic relationship, or as a pathogen or parasite to their host. While unique, each interaction reflects the adaptability of fungi and their importance in nutrient cycling, forest ecology, and plant health.

Decomposers (Saprotrophic Fungi) Break down dead organic matter such as fallen leaves, wood, and plant debris, recycling nutrients back into the soil.

Decomposer fungi play a critical role in forest ecosystems by breaking down dead organic matter such as fallen leaves, logs, and plant debris. This process recycles nutrients back into the soil, enriching it for future plant growth. In Trinity County, several mushrooms act as decomposers. Lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus), for example, grows on dead or dying hardwood logs and is known for its cascading white spines. Turkey tail (Trametes versicolor), another common decomposer, forms colorful, fan-shaped brackets on decaying wood and is widely recognized for its medicinal properties. These fungi accelerate the decomposition of lignin and cellulose, substances that are otherwise slow to break down, making them essential for maintaining soil health and supporting the forest’s nutrient cycle.

Symbiotic fungi (mycorrhizal) Form mutualistic partnerships with plant roots, exchanging water and minerals for sugars produced by photosynthesis; this relationship is critical for forest health.

A symbiotic relationship between trees and mushrooms is a mutualistic partnership where both organisms benefit. Most edible and forest mushrooms form mycorrhizal associations with tree roots. In this relationship, the mushroom’s underground network of filaments (mycelium) attaches to the tree’s root system. The tree provides the fungus with carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis, while the fungus helps the tree absorb water and essential minerals like phosphorus and nitrogen from the soil. This exchange strengthens tree health, improves soil structure, and supports the growth of the mushroom. These partnerships are species-specific as certain mushrooms only pair with particular trees, such as chanterelles with Douglas fir or boletes with pine and fir.

Pathogens or Parasites Infect living plants or trees and sometimes cause disease—these are often referred to as fungal pathogens.

Unlike decomposers, pathogenic or parasitic fungi infect living plants or trees, often causing disease or structural damage. These fungi extract nutrients from their hosts, sometimes weakening or killing them. In Trinity County, an example is west coast reishi (Ganoderma oregonense), which causes white rot in living trees and can eventually lead to tree failure. While these fungi can be harmful to individual trees, they also play a role in forest dynamics by creating gaps in the canopy that allow new growth and biodiversity.

Common Mushrooms in Trinity County – By Forest Type

Finding mushrooms in Trinity County changes dramatically with the seasons. Knowing when and where to look is key for successful and safe foraging. Each season brings different species that thrive under specific forest conditions and tree associations. This guide outlines the most common mushrooms found in the county, their preferred habitats, and identification tips to help you distinguish between varieties.

Riparian Hardwood Forests

The Riparian Hardwood Forests are primarily situated alongside rivers or streams with varying degrees of proximity to the water’s edge. These ecosystems connect aquatic and upland areas through dynamic water flow. Various plant species thrive in different hydrologic zones based on their dependence on water. In Trinity County the streams and rivers that comprise riparian areas are the Trinity River, North Fork Trinity River, South Fork Trinity River, not to mention smaller creeks like Coffee Creek, Canyon Creek or Hayfork Creek. Hardwood tree species that are found in riparian river corridors are cottonwoods, like black and Fremont cottonwood, Oregon ash, white alder (the most common riparian tree) and tree willows like red and shiny willow. It is vitally important to understand and identify riparian trees when mushroom hunting.

Yellow Morel (Morchella americanna)

Riparian morels (Morchella species) emerge after the first warm rains, typically March through May. A prized edible that grow with cottonwood, Oregon ash and apple trees here in Trinity County. They are known to populate disturbance areas affected by flood, fire or fallen trees.

Identification Tips:

- Honeycomb-like cap with pits and ridges.

- Hollow stem and cap when sliced open – a key indicator of a true morel.

- Colors range from tan to dark brown.

Other morels that occur with cottonwoods: Various black morels (M. norveginesus, M. brunnea, M. populiphila )

A related species to the morel that may indicate you are slightly early in your search for true yellow morels. Like the yellow morel, the thimble cap occurs with cottonwood species and is as thought to be as delicious as the yellow morel yet restricting consumption of this mushroom is advised (iNaturalist)

Identification Tips:

- Wrinkled cap (versus honeycomb-like) with pits and ridges

- Pithy filled stem that goes all the way to the cap when sliced open

- Colors range from tan to dark brown.

Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus spp.)

Oyster mushrooms, often seen in restaurant dishes, grow on riparian hardwoods like cottonwood, ash, willow, and alder. They are a safe choice for beginner foragers due to the lack of dangerous look-alikes.

Identification Tips:

- Gills run all the way down its stem

- Grows on trees (versus in the ground)

- White, creamy or tan in color

Honey Mushroom (Armillaria spp.)

Honey mushrooms are a parasitic mushroom that infects their host as they feed from it. It is only edible if cooked significantly well, otherwise if undercooked it can make you sick.

Identification Tips:

- It grows in big clusters at the base of the tree.

- Gills run slightly down the stem.

- Has a prominent skirt on the stem called an annulus

Low Elevation Mixed Conifer-Hardwood Woodland

Moving away from the rivers and into the low elevation mixed woodlands look for Douglas fir (Psuedotsuga menziesii), Tanoak with populations in western Trinity and Coffee Creek, madrone and Ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa). Most mushrooms in this area will populate in the early fall with first rains and prior to frost or snow.

Cascade Chanterelle (Cantharellus cascadensis)

Chanterelles are a mycorrhizal associate with Douglas fir and true fir trees and if found make for a prized edible when found. Look for chanterelles in the fall after the first rains. The cascade chanterelle (Cantharellus cascadensis) does have poisonous look-alikes to watch out for, including the Jack O’ Lantern (Omphalatus olivescens) in Trinity County and others not yet found in Trinity such as the False Chanterelle (Hygrophoropsis aurantiaca).

Identification Tips:

- Has ridges or false gills that run down the stem.

- Grows with Douglas fir out of the ground (not from the wood)

- When cut in half, the flesh is orange outside and white inside

- Should not be confused with the Jack-o-Lantern mushroom or False Chanterelle.

Jack O’ Lantern (Omphalatus olivescens)

A showy beautiful mushroom that grows at the base of oak trees attached to the wood itself. The Jack O’ Lantern mushroom can make you very sick if ingested and can be confused with the cascade chanterelle.

Identification Tips:

- True gills, bladelike structures.

- When cut in half, the flesh is orange all the way through.

- Grows from the wood of oak trees.

- Should not be confused with the cascade chanterelle.

White Chanterelles (Cantharellus subalbidus)

White chanterelles are symbiotic with Douglas fir and tanoak trees and like the orange chanterelle make for a prized edible when found. Look for white chanterelles in early fall after rains but prior to freezing.

Identification Tips:

- Has ridges or false gills that run down the stem.

- White to cream colored

- Grows with Douglas fir & tanoak out of the ground (not from the wood)

- Gets soggy with rain as time progresses through the fall.

Queen Bolete (Boletus regineus)

Royal boletes, including King and Queen varieties, are prized edibles from the porcini family. They thrive in early fall rains but do not persist through winter. Typically found near tanoak and true oak, these mushrooms form strong mycorrhizal bonds with roots, enhancing tree health and soil nutrient cycling.

Identification Tips:

- Pores instead of gills

- Has a whitish bloom on the cap when young

- Stem shows a prominent netting (reticulation)

Black Trumpets (Caterellus calicornucopoides)

Black trumpets are more common in Western Trinity County than other areas due to the mushrooms relationship with tanoak. These saprotrophic mushrooms decompose dead organic matter, recycling nutrients into the soil and can also be found near black oak, and live oak. They grow in the winter months and can be recognized by their distinct color, shape, and smell.

Identification Tips:

- Color is black, grey or sometimes dark brown

- Look like trumpets with wavy edges rolled outwards.

- Hollow from the base to the edge.

- Does not have gills or pores.

Oak Woodlands

Oak woodlands are another lower elevation forest of Trinity County made up of trees such as white oak, black oak and blue oak. In these types of forests, most mushrooms in Trinity County grow with black oak, so learning to identify this tree is important when foraging!

Butter Boletes (Butyriboletus spp.)

Butter boletes fruit under white and black oaks in the early fall after early season warm rains.

- Bright yellow stem & pores

- Spongy underside and a bulbous stem

- Bruise blue when nicked on the pore surface versus on the inside

Oak Satan Bolete (Rubroboletus eastwoodiae)

Beautiful yet very toxic mushroom that will fruit under oaks at the same time as butter boletes.

- Red pores and cap

- Bruises blue on the inside when bisected

- Spongy underside and a bulbous stem

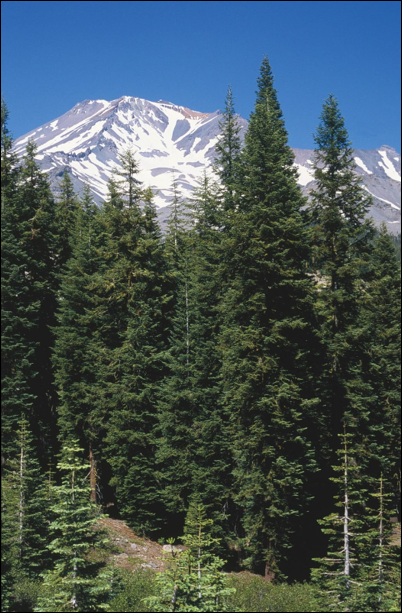

High Elevation Conifer Forests

High elevation conifer forests are characterized by dense stands of evergreen trees, primarily conifers such as white fir, Shasta red fir and sugar pine. These forests typically occur at elevations above 3000 feet and are often found on steep, exposed slopes.

In the Trinity Alps, upland morels are the most commonly found edible mushroom. Some species of morels thrive in areas affected by wildfires. The nutrient-rich soil created by fires fosters morel growth, usually within one to two years after a burn but some species don’t appear until several years post-fire. Fires reduce competition and help spores germinate, forming helpful relationships with surviving trees. This makes recent burn sites ideal for spring foraging, resulting in plentiful morel harvests.

There are about 4 to 6 species of morels that adapt well to burn areas, and although they are hard to distinguish, different species appear in these fire-affected zones at various times.

Black Morel (Morchella snyderi)

Besides the burn morels that occur 1-3 years after a burn, Morchella snyderi will be a mushroom to keep your eye out for. M. snyderi occurs in high elevation areas 3-4 years after a burn in undisturbed true fir forests, more commonly found near Mt. Shasta, but can be found in the Marbles and Trinities.

- Look for morels a few weeks after the snow has receded.

- Occurs in undisturbed true fir forests and several year old burns of the same forest type.

- Occurs in the Trinities and very common around Mt. Shasta.

Spring King Bolete (Boletus rex-veris)

Also found in the high elevation conifer forests are the King Bolete. Look for these a few weeks after the fruiting of morels in true fir forests.

- Pores instead of gills. Reticulation on stipe

- Occurs with true firs approximately 2 weeks after the morel flush.

- Often grows as shrumps.

- Not as good as fall porcini but still an excellent edible

Photos provided by Kyle Sipes – unless otherwise noted on the image.

The January 28, Science on Tap event was recorded with the presenters permission. Once the video is edited to include the slides, we will post it here!

Kiana Abel, Public Affairs Specialist

As Public Affairs Specialist for the Trinity River Restoration Program, Kiana manages external communications, media relations, and stakeholder outreach. She acts as a liaison between program initiatives and the public, transforming technical findings into compelling narratives that promote understanding of restoration initiatives on the Trinity River. Kiana holds a Batchelor’s in Art History, has spent most of her career in marketing and is focused at the TRRP on bridging the gap between public awareness and resource restoration and management.